I read Zadie Smith’s essay on language and the Israel-Hamas war. In it, we find a common trope on the contemporary left: the idea that it is valorous to put your body on the line for the thing you are protesting. She writes,

For several years now, many people have been protesting the economic and political machinery that perpetuates climate change, by blocking roads, throwing paint, interrupting plays, and committing many other arrestable offenses that can appear ridiculous to skeptics (or, at the very least, performative), but which in truth represent a level of personal sacrifice unimaginable to many of us.

In my mind, this is a totally backwards way to think about protest and mass political action. It lionizes the *harm* or *danger* to the protestors rather than focusing on *achieving the stated goal* of the protest. Taken to an extreme, people will light themselves on fire in protests with a dubious impact on achieving the stated goals. Sometimes we need to take risks to make protest effective, for sure. There are many such examples in history, and we rightly revere people who made great personal sacrifices to advance the cause of justice. But we revere them because they advanced the cause of justice, not simply because they suffered. Seeking out suffering for its own sake as evidence of effective protest is dumb and potentially counterproductive.

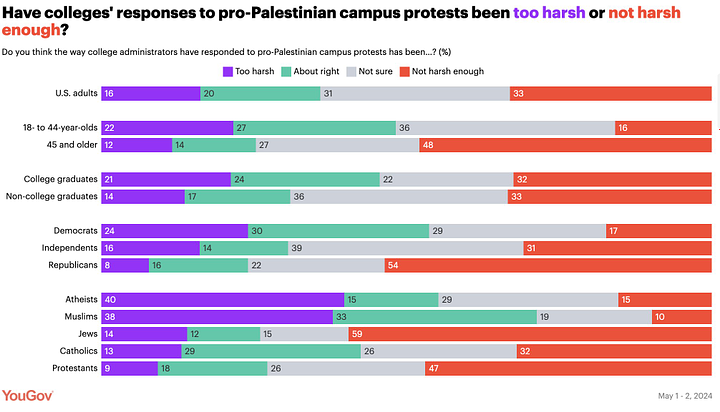

As I have tweeted frequently in recent weeks, I think we on the left need to have some real talk about the goals and methods of contemporary protest on the left. To put some data to this, here is a recent YouGov poll (May 3).

By a 47-28 share (-19), Americans oppose the protests. This includes opposition among college grads (48-38, -10) and among independents (44-24, -20). These are awful numbers for a protest that is nominally trying to persuade people to care more about the plight of Gazans. It is a first order failure for the protests, and people interested in helping Gazans should be course correcting, but alas.

More shockingly, by a 33-16 (-17) margin, Americans say that the response to the protests has been not harsh enough rather than too harsh. In other words, people oppose the protests and think the universities should call the cops more and faster.

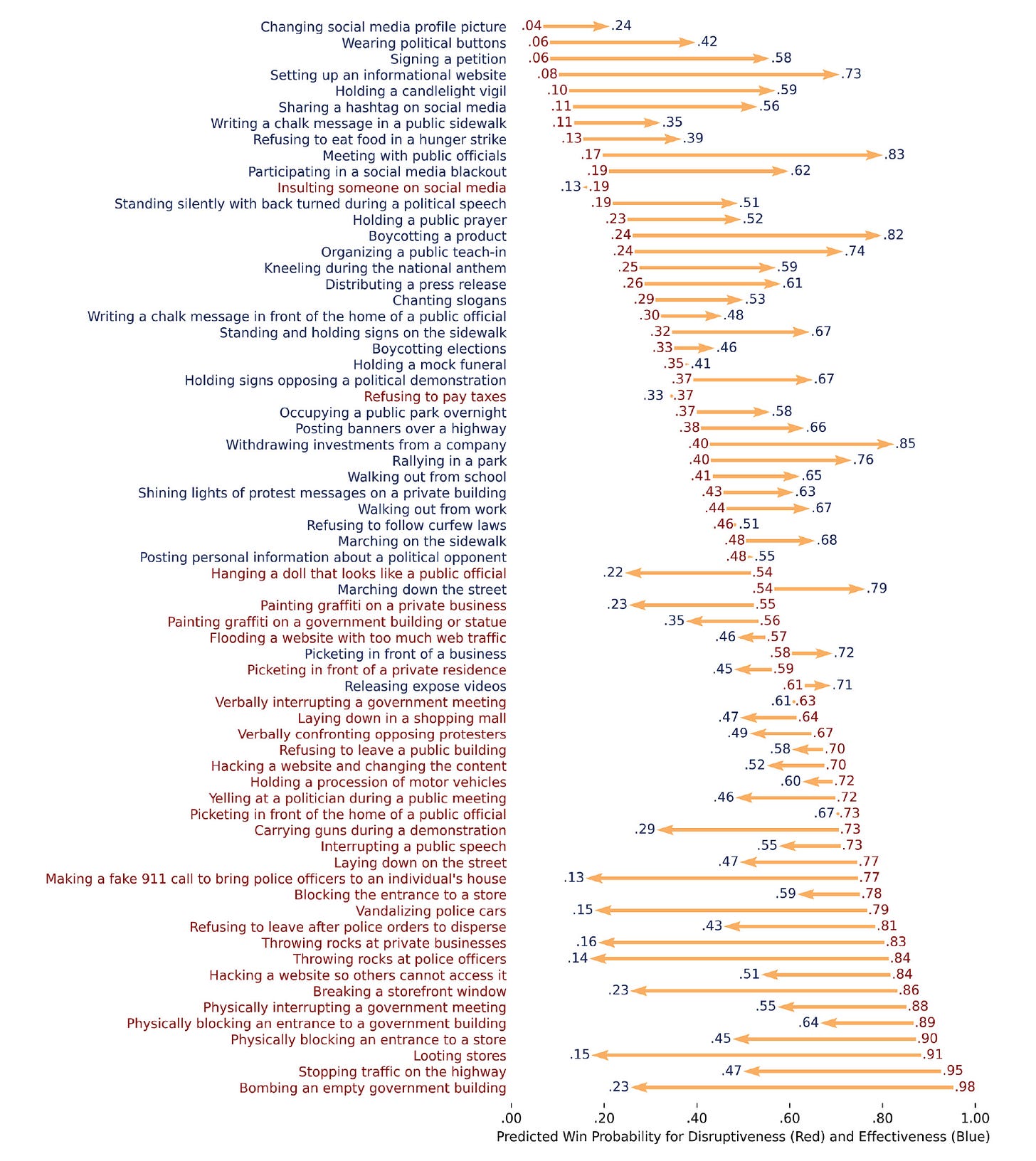

In certain circles, this fact will be used to condemn the public. But if we are doing politics realistically, we must try to convince the public rather than complain about where people are at politically. And the plain fact is that protest tactics like blocking highways and refusing to disband encampments are perceived as extremely disruptive and not effective. Here is some research polling people on perceived disruptiveness vs effectiveness, and you can see that blocking a highway, physically blocking buildings, refusing to disband when ordered, and refusing to leave a public building are all perceived as highly disruptive and not effective. This research is not perfect, it is perception rather than actual shift in public opinion, but it is strongly suggestive.

On the other end of the spectrum, candlelight vigils, meeting with officials, and traditional protests (holding signs) are viewed as effective and not disruptive. In my mind, it’s very important to be cognizant of what the public thinks when devising a protest strategy. We saw the Women’s March in 2017 was highly effective at coalescing resistance to Trump and was a massive display of political power—one of the largest marches of all time. It was covered highly favorably in the media and I think was partially responsible for the incredible 2018 midterm reaction against Trump.

The Women’s March did not focus on a local objective like a local university changing its investment portfolio, but rather on a clear national political goal (Trump bad, let’s organize to beat him at the polls). The protests acted as a show of political power and raised awareness about the dangers of Trump. And they were extremely inclusive and family friendly—I distinctly remember them being a family affair, with parents bringing their kids and random marchers being interviewed on the street and being like “I’m just here with my kids to support democracy and the rule of law.” Great stuff.

In contrast, the contemporary campus protests do not seem interested in talking to the media and getting their message out. Their demands are incredibly local (university should change its investment portfolio is the main one). And there is little coalition building—ideally you’d want a united front of like, everybody in America for peace in the Middle East, which includes a Palestinian state. But campus protestors want their universities to also cut ties with Jewish student groups and random (or all) Israeli universities.

So the situation the students are in is they are doing a very personally costly protest that could get them thrown out of college and prosecuted, where they have not managed to convince the public of their side (and are actively turning people off to the cause they say they support), and where their demands are not ambitious and universal but instead are hopelessly parochial. Even if all of the student demands are achieved, it is highly unlikely to matter for the cause of justice for Gazans. I wonder what it’s all for.

And in the midst of this, instead of academics writing to their students encouraging them to channel their horror at the human rights abuses in Gaza in a more productive direction (effective protest and politics), we have a debate in the academy about whether universities should actually divest. This makes the naval gazing cycle complete. The goal here should be to stop a war and secure peace for Israelis and Palestinians. If you are serious about that goal, you don’t spend your time debating policies that are irrelevant to that goal. Instead, you do all the normal politics things—persuasion, activism, lobbying, coalition building, etc. specifically in support of your goal.

Anyway, as I’ve tweeted a bunch, and written in the past, these are young adults who are not political experts. It’s completely fine for them to make some dumb mistakes, and we should be forgiving and understanding as a society. But also, these are kids at super elite schools and somebody at these super elite schools should be giving politically active kids sensible advice about how to do political action! It is a knowable thing, not a mystery! In closing, I hope to see more op-eds from professors about how students can better advocate for the rights of Gazans and fewer about the relative merits of divestment.