This is the third post in the doomed ideologies series. Check out the first and second posts if you missed them. Please subscribe to good and bad ideas to follow along.

This is my third and final post about degrowth. In this post, I want to talk about a proiminent rhetorical strategy degrowthers use, which I call underspecification. In the previous two posts, we have seen that degrowthers do not have an alternate economic vision that makes sense, and do not take the political challenges of large-scale change seriously.

On top of these substantive issues with degrowth, advocates insulate themselves with obfuscatory rhetoric. It is in fact difficult to figure out what degrowthers are saying. This does not mean anybody is consciously choosing to use unclear language, but rather that the evolution of discourse has made vague degrowth rhetoric a strategy that like, gets degrowthers on podcasts and stuff. It is a successful rhetorical strategy, and success tends to replicate.

what is underspecification

Let’s say you are crafting an argument and your highest priority is to never be wrong. You might go about it like this.

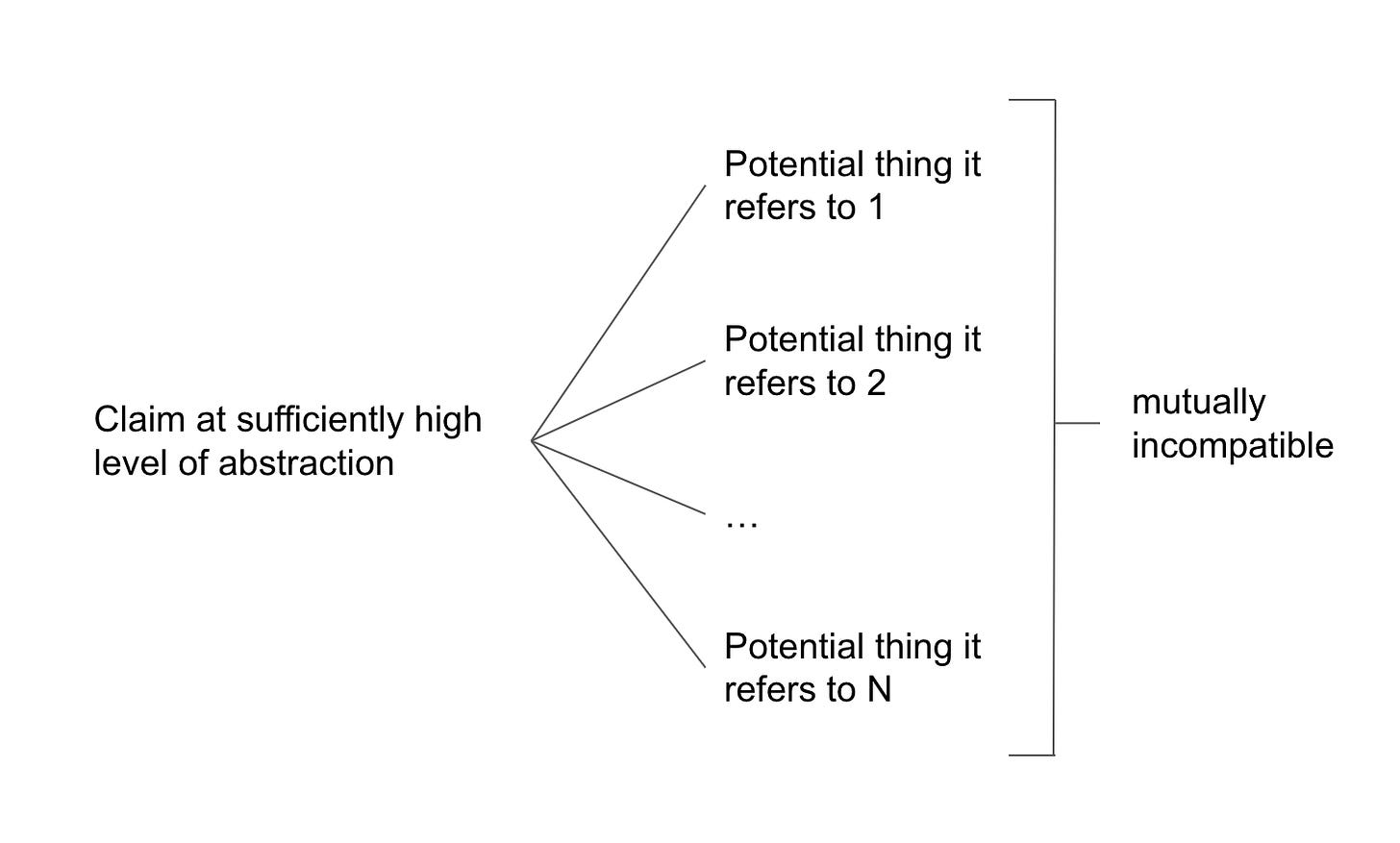

That is, you keep your main argument relatively abstract (or use overly complex academic-speak, etc), so that there is a variety of specific things that could be implied. The potential specifics of the argument don’t need to be consistent with one another, in fact in this model they are not mutually compatible. You can then swap out specifics depending on the context to suit your immediate argumentation needs. What you are doing is not affirmatively crafting a consistent body of thought, you are reacting to specific interlocutors by pulling out specific arguments to defeat them.

A crazy thing about this rhetorical strategy is that it can fool proponents. Degrowthers may in fact believe (and probably do believe) that their worldview answers all the questions. But what is actually going on is there are mutually incompatible, contextually-supplied answers.

Let’s look at an example by returning to a high level summary of degrowth we have looked at before:

Researchers in ecological economics call for a different approach — degrowth. Wealthy economies should abandon growth of gross domestic product (GDP) as a goal, scale down destructive and unnecessary forms of production to reduce energy and material use, and focus economic activity around securing human needs and well-being.

The proposal to “focus economic activity around securing human needs and well-being” is a great example of an underspecified proposal. What does “securing well-being” mean in this context? The answer is: not much until you ask what it means.

At that point, someone arguing for degrowth can define “well-being” to be appropriate to the specific discourse context they are in. So, if you are talking to leftists who think we should all use community washing machines, you can say well-being is really about re-focusing ourselves on community activities like going to the laundromat together. Or, if you are talking to a bunch of normies who really like their personal washing machines, you can say that well-being is really about ending planned obsolescence for washing machines so your washing machine will last for 100 years.

You are not actually proposing anything concrete with this rhetorical strategy. You are simply adapting a general and impossible-to-argue-with principle like “well-being is good” for a specific context, where your adaptation gets you plaudits in-context.

“that’s not really what degrowth is”

I think this rhetorical strategy provides an explanation for Ezra Klein’s astute observation that “it’s tricky to talk about [degrowth]… because its advocates will continue to say you’re defining it wrong.” This actually makes a lot of sense if you think of degrowth as a set of underspecified but hard-to-disagree-with statements where the details are filled in situationally. In some contexts, degrowth sounds a bit like green growth, and in others it sounds a bit like a Leninist revolution.

I think it’s better to view degrowth as a set of underspecified statements than an ideology with actual proposals. Who would disagree with the statement that “we should end destructive industries”? Sure. But a proposal like that is all about the details. Degrowth rarely affirmatively engages with these details.

When criticism arises of a general claim, degrowthers can say “that’s not really what we mean” and point to a different set of specifics for that claim. In this way, degrowthers do something which I’m going to call criticism-matching.

When you see criticism 1, you say the claim is actually about potential thing 1 because potential thing 1 rebuts criticism 1. Same for criticism 2, and so on. If people criticize potential thing 1 directly, you can say “no, no, we actually mean potential thing 2 for this claim,” and then people need to spend time assessing potential thing 2. It’s a nice trick, huh?

This strategy of underspecification and criticism-matching is also consistent with the recommendation to read more and understand better from degrowthers. It’s true that if you criticize degrowthers (as I have done) for something like wanting to reduce labor productivity, degrowthers can dig something up to say that’s not really what we mean, you misunderstand degrowth. Sure, fine, whatever.

Rather than playing this argumentation game, I think it’s much better to insist that degrowthers reduce their level of abstraction from The World System to, you know, specific trends and policies. Then, we can argue about those specifics and have a grounded conversation. But as long as it’s not really clear what degrowth’s more abstract principles really mean, degrowthers will always be able to point to some paper, somewhere, which proves you wrong.

As a final note on degrowth, I think this particular rhetorical strategy works because degrowth is an ideology of permanent critique. It is a doomed ideology in the sense that if you tried to do its major proposals you would cause economic, social, and political disasters. But it is rhetorically very alive in the academy right now, and that life I think is enabled by the particular rhetorical strategies I’ve outlined here.